Understanding the Tariff Impact on Trade Balances: A Path to Barter Economy?

in Hot Takes, Tariff Policy, Trade Deficits, Trump Administration, All Posts

We’ve now seen Elon Musk blast Peter Navarro, highlighting their conflicting views on trade, following the matchlighting of trillions of dollars of retirement accounts. Things seem to be chaotic, and who knows where this tariff strategy will lead. One thing I keep hearing is that we need to have a zero trade balance with all of our trading partners. To quote President Trump on the trade deficits: “A deficit is a loss. We’re going to have surpluses, or we’re, at worst, going to be breaking even.” This struck me as an odd statement because trade imbalances are not really like a profit and loss statement.

What was also strange is the formula they misused. Economist Brent Nieman, who created the formula, was in the news saying that the administration misunderstood its application. When you see how they used it, it points to this concept that a zero trade balance can be achieved with tariffs.

If you follow this to the final move on the chessboard, all of roads that lead to a zero trade balance with every trading partner means we are in a barter economy. It’s a leap you need to take to get to this conclusion but it’s not an unreasonable end state if you take all of this at face value. Let me explain.

TL;DR

The Trump administration’s goal of achieving zero trade deficits with all trading partners ignores some fundamentals of global trade and also leads to a strange economic conclusion involving barter economics. By using incorrect values in Brent Neiman’s tariff formula, they’ve calculated artificially high tariff rates. Take a few logical steps from this premise and following through to a conclusion, forcing bilateral trade balances would essentially return us to a barter economy, where countries can only receive goods by directly exchanging equal-valued goods – an inefficient system we abandoned a long time ago. Modern economies naturally have trade imbalances because they allow specialization, comparative advantage, and the flow of both goods and capital. Rather than viewing deficits as “losses,” we should see them as features of a complex, beneficial global trading system.

The Trump Administration’s Tariff Policy

The Trump administration’s approach to tariffs has been both bold and controversial. Aimed at reducing the U.S. trade deficit, the administration has imposed tariffs on a wide range of imported goods from countries with which the U.S. has significant trade deficits. The rationale behind this policy is to level the playing field for American businesses and workers who face foreign trade barriers and what the administration deems as unfair trade practices.

However, this tariff policy has not been without its critics. Many argue that the tariffs could lead to higher prices for consumers, as import duties make foreign goods more expensive. This, in turn, could reduce economic growth by increasing costs for businesses that rely on imported materials. Additionally, there is concern that these tariffs could spark trade wars with other countries, further complicating international trade relationships.

Critics also point out that the tariffs do not address the root causes of the trade deficit, such as the strong U.S. dollar and the country’s low savings rate. These underlying issues mean that even with tariffs, the trade deficit may not significantly decrease. Instead, the focus should perhaps be on broader economic policies that encourage savings and investment within the U.S.

The Misunderstood Formula

At the heart of the current tariff policy is a formula developed by Brent Neiman:

Δτᵢ = (xᵢ – mᵢ)/(ε φ mᵢ)

Where Δτᵢ represents the tariff rate on a foreign country, xᵢ – mᵢ represents the trade deficit (exports minus imports), and the denominator contains two critical factors: epsilon (ε) and phi (φ).

The administration apparently assumed that epsilon and phi would effectively cancel each other out, leading to substantially higher tariff rates than the formula was designed to produce. For instance, the Japan tariffs were calculated at 46% using an epsilon value of 1 and a phi value of 0.25. However, Neiman has argued that phi should actually be 0.95, which would reduce that 46% tariff by nearly a factor of 4. Yielding about a 12% tariff to Japan.

This mathematical approach illustrates the technical application of a useful formula to justify a desired outcome: Trade deficits should be eliminated entirely.

Trade Deficit Imbalances in Everyday Life

To understand why the concept of a zero trade balance is problematic, let’s consider some everyday examples.

Imagine an Apple Store employee. Each month, she extracts capital from Apple in the form of her salary. Does she then turn around and spend her entire paycheck on iPhones, MacBooks, and Apple Watches? Of course not. If we applied the zero-balance trade logic to her situation, she would need to purchase thousands of dollars of Apple products monthly to “balance” her trade with her employer. This is obviously unrealistic and economically nonsensical.

Similarly, consider a cashier at Whole Foods. How many organic vegetables and specialty cheeses would he need to purchase during his shifts to achieve a trade balance of zero with his employer? The answer is an impossible amount relative to his needs and income.

These examples may seem simplistic, but they illustrate an important point: trade imbalances are a natural and necessary feature of economic specialization and the division of labor. In contrast, free trade principles advocate for the natural flow of goods and services based on comparative advantage, without the need for a zero-balance trade.

International Implications

Now, let’s scale this up to international trade. How many US-made cars would Sri Lanka need to purchase from the United States to offset the textiles that American consumers buy from Sri Lankan manufacturers each year?

The reality is that countries specialize in producing different goods and services based on their competitive advantages, resources, and economic development. The World Trade Organization facilitates these global trade agreements, ensuring that member nations adhere to agreed-upon tariff rates and trade practices.

Sri Lanka has a comparative advantage in textile production, while the U.S. has advantages in high-tech manufacturing and services. Forcing a zero trade balance would require Sri Lanka to drastically reduce its textile exports or somehow find the means to purchase an equivalent value of American goods—neither of which would benefit either country.

Let’s look at the US-car to textiles trade comparison more closely.

Sri Lankan transport is dominated by scooters because that’s the affordable transportation means for the country’s stage of economic development. I am sure many Sri Lankans would love to drive a Ford F150 but the number of people who can actually afford one is self-evident; just look at how many scooters there are compared to cars. Annual car sales are about 10,000 units and motorcycle and scooter sales are over 10x that figure. It’s just not possible to balance the trade given what Americans need and what Sri Lankans need.

How can this be reconciled?

The Impact of Tariffs on Trade Relationships

The imposition of tariffs by the Trump administration has had a profound impact on trade relationships between the U.S. and its trading partners. Countries like China and Canada, which have been significant targets of these tariffs, have seen a decline in trade with the U.S. This has had serious repercussions for businesses and workers in these countries, many of whom rely heavily on trade with the U.S. for their livelihoods.

The tariffs have also led to a decrease in foreign investment in the U.S. The uncertainty and unpredictability of the administration’s trade policy have made many foreign companies hesitant to invest in the U.S. This decline in foreign investment has significant implications for the U.S. economy, which depends on such investments to help finance its trade deficit.

Moreover, the tariffs have strained diplomatic relationships, as affected countries have responded with their own tariffs and trade barriers. This tit-for-tat escalation has created a more hostile international trade environment, making it more challenging to negotiate trade agreements and resolve disputes.

The Impact of Tariffs on Specific Industries

The Trump administration’s tariff policy has had notable effects on specific industries, particularly the automotive and technology sectors. These industries are heavily reliant on imported goods and materials, and the tariffs have led to higher prices for both businesses and consumers.

In the automotive industry, tariffs on imported steel and aluminum have increased production costs for car manufacturers. This has led to higher prices for American-made cars, making them less competitive both domestically and internationally. Additionally, tariffs on imported auto parts have disrupted supply chains, further increasing costs and complicating production processes.

The technology sector has also felt the impact of tariffs, particularly those on electronic components and devices. Higher import duties on these goods have increased costs for tech companies, which often rely on global supply chains to source parts and manufacture products. This has led to higher prices for consumers and has slowed economic growth in the sector.

Overall, while the Trump administration’s tariff policy aims to protect domestic industries and reduce the trade deficit, it has also introduced significant challenges and uncertainties for businesses and consumers alike. The long-term effects of these tariffs on the U.S. economy and its trade relationships remain to be seen.

The Road to Barter

If we follow the zero-balance trade philosophy to its logical conclusion, we arrive at a startling realization: we’re advocating for a return to a barter economy.

In a barter system, goods are directly exchanged for other goods without the intermediate use of money or capital flows. Such a drastic shift could be seen as a national emergency, given the significant impact on economic stability and national security. The last time the world economy operated primarily on barter principles was before the widespread adoption of currency thousands of years ago—a system that was abandoned precisely because of its inefficiency and limitations.

Barter economies struggle with the “double coincidence of wants” problem: I must want what you have and you must want what I have, in proportions that satisfy both of us, for a trade to occur. This severely limits economic activity and specialization.

Modern global trade evolved beyond barter precisely because capital flows—investments, loans, currency exchanges—allow for the efficient movement of goods and services without requiring immediate and direct exchange. Trade deficits and surpluses are a necessary feature of this system, not a bug.

Why Zero-Balance Trade Leads to Barter

The concept that a zero-balance trade philosophy leads to a barter economy follows from understanding the fundamental nature of modern trade and capital flows.

In our modern economy, trade imbalances serve a crucial function. When Country A imports more from Country B than it exports to that country, this “deficit” is actually part of a larger global flow of goods, services, and capital. These imbalances aren’t accounting errors – they’re features that allow specialization and efficient resource allocation.

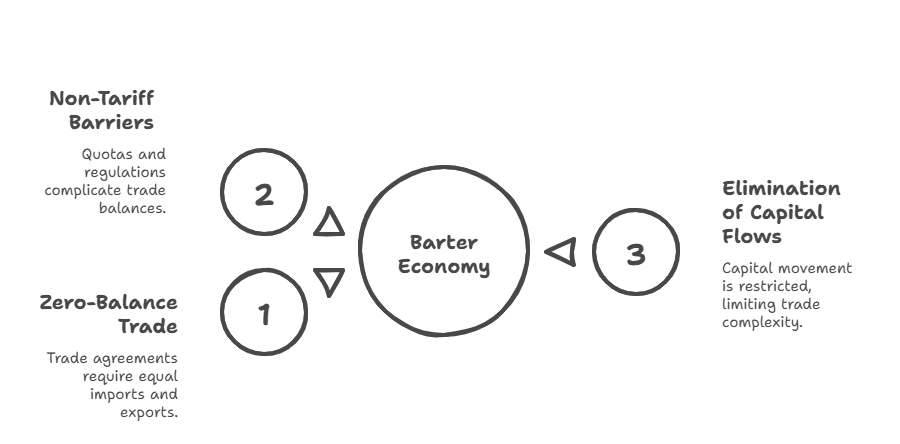

If we mandate that every bilateral trading relationship must have a perfect balance (imports = exports), we effectively eliminate the role of capital flows in international trade. Here’s why this leads to barter:

- In a zero-balance world, every exchange must be directly offsetting. Additionally, non-tariff barriers such as quotas and regulations further complicate achieving a zero-balance trade. The US can only buy $10 billion of goods from Japan if Japan buys exactly $10 billion of goods from the US.

- This eliminates the multilateral nature of trade. Currently, the US might run a deficit with Japan but a surplus with the UK, with capital flowing between all three countries in complex ways.

- Without capital flows, we’re left with direct exchange of goods for goods – the definition of barter.

- Money still exists in this scenario, but it functions merely as an accounting unit rather than as capital that can flow independently of goods.

Modern trade works specifically because we don’t need direct, bilateral balance. Capital can flow where it’s most productive, and goods can move according to comparative advantage without being constrained by the requirement that each trading pair must perfectly balance.

Forcing zero balances means each country can only get goods from another country by directly providing equal-valued goods in return – precisely how barter economies function.

The Real Purpose of Free Trade

The fundamental misunderstanding embodied in the “zero deficit” approach is that it views international trade as a competitive game with winners and losers, rather than a cooperative system that creates value for all participants.

The purpose of trade is not to achieve a perfect balance sheet with every trading partner. Instead, trade should be viewed as a win-win scenario where all parties benefit from the exchange of goods and services. Rather, it’s to increase overall prosperity by allowing each country to specialize in what it does best, while obtaining goods and services that others produce more efficiently.

When we import more than we export from a particular country, we’re not “losing”—we’re acquiring goods that improve our standard of living. These imports are paid for not just with our exports to that specific country, but through the complex web of global trade and capital flows.

Conclusion

If we somehow achieved the goal of perfect trade balance with every partner, we would effectively be regressing to a primitive barter system—a system humanity abandoned millennia ago because it constrained rather than enhanced prosperity.

Am I saying that is really going to happen? No. That would be very unlikely. Nonetheless, the premises we are hearing about do lead to that strange outcome if you follow it to a logical conclusion.

In order to get the views on these issues more aligned with a fix that can work, instead of viewing trade deficits as “losses” to be eliminated, we should recognize them as reflections of the complex and beneficial patterns of specialization and exchange that make modern economic prosperity possible. Maintaining robust domestic production is crucial for economic stability and national security, ensuring that the country can meet its own needs without excessive reliance on foreign imports.

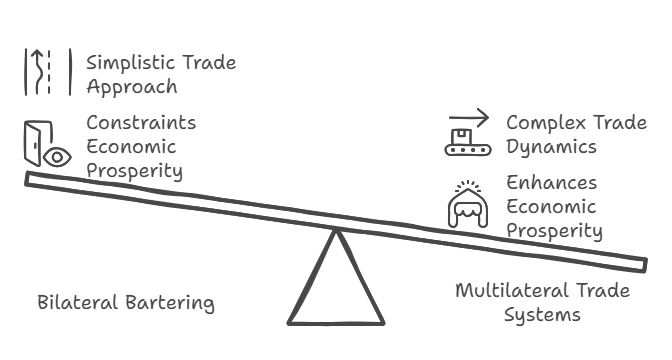

The path forward lies not in retreating to bilateral bartering, but in addressing legitimate trade concerns within the framework of a sophisticated, multilateral trading system.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Aren’t trade deficits bad for the American economy? Why shouldn’t we try to eliminate them?

A: Trade deficits aren’t inherently “bad” – they’re simply one part of a complex global economic system. When we import more than we export from a particular country, we’re obtaining goods that improve our standard of living, often at lower costs than if we produced them domestically. These imports are paid for through our multilateral trade relationships, not just bilateral ones. Rather than viewing deficits as “losses,” they should be seen as reflections of comparative advantage, specialization, and efficient global resource allocation. Trying to eliminate all deficits could actually harm American consumers through higher prices and reduced choice.

Q2: If we implement tariffs, won’t that force other countries to buy more American goods?

A: Tariffs aren’t a magic solution for increasing exports. When we impose tariffs on imports, we make those goods more expensive for American consumers and businesses. Other countries typically respond with retaliatory tariffs on American exports, creating a lose-lose scenario. More fundamentally, countries buy American goods based on their needs, preferences, and economic capacity – not because of trade policies. As the Sri Lanka example shows, many developing countries simply don’t have the economic capacity to purchase high-value American goods in quantities that would balance our imports from them, regardless of tariff levels.

Q3: How does the administration’s misapplication of the Neiman formula affect real-world trade?

A: By incorrectly assuming that the epsilon and phi variables in Neiman’s formula would cancel each other out, the administration calculated much higher tariff rates than the formula was intended to produce. For example, the Japan tariff was calculated at 46% using a phi value of 0.25, when Neiman argues it should be 0.95 – which would reduce the tariff by nearly a factor of 4. These artificially high tariffs create unnecessary economic friction, raising prices for American consumers and businesses while potentially triggering retaliatory tariffs that harm American exporters. It demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of trade economics and the purpose of Neiman’s formula.

…

Salvatore Tirabassi is the Managing Director at CFO Pro+Analytics, with over 24 years of experience in venture capital, private equity, and executive financial leadership. He has raised over $400 million in capital throughout his career and helped dozens of companies optimize their financial strategy for growth and value creation.

For a FREE 20-minute consultancy session CLICK HERE!